Day of the Dead in Mexico, November 2nd

In the prehispanic world, the concept of death played a fundamental role, most of the rituals and even daily life referred to the will and action of the gods of the underworld. Gods like Mictlantecuhtli, Coatlicue, Cihuateteo, Tepoyolotli and Chalchiutlicue were worshiped because they defined the destiny of the dead.

Although there was an essential difference among social classes, each had different rituals bringing the dead close to their deities. Thus, those of greater rank belonged to important personalities as the warrior population, artisans and priests. In each there were objects related to the activity of the dead. In the tombs found inside the Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacán, diverse ceramic objects, funerary urns, incense, etc., have been found and are representative of the societyâs interest in preserving the underworld in the most ideal conditions for completing their passage.

In each of the cultures developed among prehispanic Mexico, death had a central role, for which it is not strange to find in the burials of Maya, Toltec, Zapotec and others, spaces designed to contain human remains and specially, rituals with the goal of easing the passage and even the defeat of adverse forces to the final destination reached alongside the gods of the universe.

After the arrival of the Spaniards, for the process of evangelization, it was much simpler to adopt many of the prehispanic beliefs than by the will of the church or imposition of Indian groups, because they didnât fully accept the radical modification of their ideas, thus creating their own concept of the Christian dogma regarding death, resurrection, paradise, where the role of life beyond death preexisted in a natural way due to the ancestral cultural load.

Within the syncretism of the colonial phase, death also acquired a festive, dual and complex character. On the one hand, the role of the living is to help the passage of the dead to paradise, a better life, but not fully detached because it must return on the date of the faithful departed to spend time with the living, family and friends who remember them.

It is crucial to remember the thoughts of Octavio Paz regarding death in Mexican culture. He reminds us that Mexicans have a familiar relationship with death. They play with it in puppets and chickpea burials, from the coffin emerges a joyful cadaver with a bottle in hand; they eat sugar skulls engraved with their own name on the forehead or the bread of the dead; they rejoice with the special tabloids, âlas Calaverasâ which comment in satirical verse the activities of known persons at their supposed moment of their death.

On the day dedicated to the dead, altars are placed with food and candy, adorned with flowers, candles and incense laid out to smother with attentions the spirit of disappeared family members. The tombs are adorned and watched, accompanied by music.

For Mexicans, heirs to prehispanic cultures free from the terror of hell, death is not a refusal of death, but a complementary part of it, something necessary for vital energy to have a stronger rebirth.

Throughout Mexico, each town has developed this celebration in their own particular way. Within the Indian cultural frame of Michoacán, people prepare to celebrate the traditional Wake for the Dead on the night of November 1st, splendorous ritual attracting thousands of national and foreign tourists for its organization and color.

The world of the dead in Michoacán is not an artificial and staged manifestation of the alive during the ritual, but a vocation of those who, in a trait of pagan-religious belief, take offerings to the tombs, in symbol of memory and presence, to their physically absent loved ones.

The spectacular nocturnal event has dragged a profound afterlife solemnity in many towns, mainly influenced by the swamps, where the Purepecha live. Here, beyond pain and tears, it is a celebration, party and tribute to death. It is not a tragedy, it is happiness. For Indians from Michoacán the dead eat, speak, walk, go on trips and communicate with the living. For them, death is eternity and life is only a passage to the true world of light.

As in yesteryear, today nearly 30 Indian groups of the Purepecha, Nahuatl, Mazahua and Otomi ethnics live in a party ambiance. The souls of afterlife get ready for presenting themselves and the living congregate around the mortal remains of the disappeared.

Outstanding for their deeply-rooted tradition are the celebrations at Janitzio Island and the towns of Pátzcuaro, Tzintzuntzan, San Pedro Tzutumutaro, Ihuatzio and Jarácuaro, as well as Mixqui, Xochimilco and the State of Mexico, where thousands of visitors come together for contemplating this impressive spectacle.

Octavio Paz was of the opinion regarding the culture of death that, through the festivity, society frees from the norms it has imposed. It laughs at its gods, principles and laws: it denies itself. It is a revolt through which Mexicans open, participate, and come into communion with their fellow men; even with the dead and the values that give sense to their religious or political existence. Death is a mirror reflecting the vain gestures of life. All the multicolored confusion of the acts and attempts of each life, they find in death.

Click on the PLAY button to watch the Video.

Artículo Producido por el Equipo Editorial Explorando México.

Copyright Explorando México, Todos los Derechos Reservados.

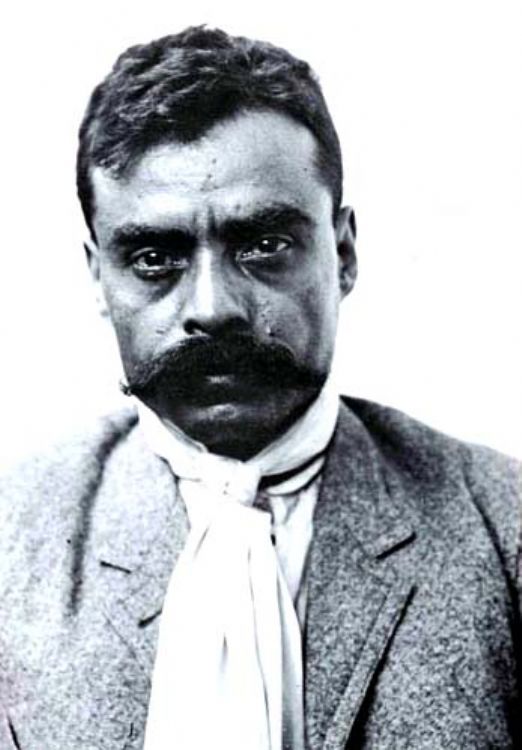

Foto: Esparta